With a number of conferences dedicated to the subject and the publication of the Taylor Review, Lammy Review and The State of Youth Justice 2017 report within months of each other, the past year has seen youth justice come to the fore of calls for criminal justice reform.

Youth justice today

The youth justice system has seen an 82% decrease in the number of children entering the system[1] since 2007, while the number of children prosecuted at court has reduced by 69%.[2] There are currently around 900 young people in custody[3] compared to peak of 2,932 children in custody in 2008.[4]

Dr Tim Bateman of the National Association for Youth Justice (NAYJ) suggests that this reduction in the number of young people entering the youth justice system is due to a “process of ‘attritition’ whereby offences committed by children are progressively filtered before reaching the stage where they are caught in the data for dedicated crime.”[5]

Even with the progress made in diverting children from the youth justice system, there remain a number of issues of concern. Despite only making up 14% of the population of England and Wales, BAME people make up 40% of young people in custody. As highlighted by the Lammy Review, “there is a greater disproportionality in the number of Black people in prisons here than in the United States.”[6]

Other groups of young people with complex and multiple needs are overrepresented in the youth justice system:

- Looked-after children make up 30% of boys and 44% of girls in custody.[7]

- Over a quarter of children and young people in the youth justice system have a learning disability while 60% of boys in custody have specific difficulties in relation to speech, language or communication. [8]

- Around 39% of children and young people in custody have been on the child protection register or experienced neglect or abuse.[9]

In light of these entrenched challenges, Khulisa calls for a move from a justice approach to children who offend to a child-focused approach based on youth welfare; one that responds to and addresses the needs of children with complex and multiple needs.

Preventing reoffending: Diversion

68% of young people who serve custodial sentences go on to reoffend within 12 months of release.

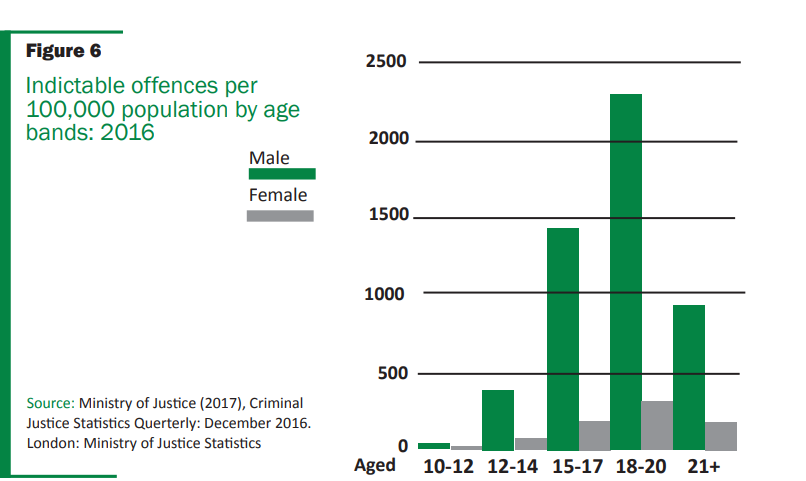

Custodial sentences affect almost all objective factors that prevent recidivism the most important of which are: family relationships, education and employment prospects and housing. This is reflected in reoffending rates: 68% of young people who serve custodial sentences go on to reoffend within 12 months of release.[10] Comparatively 62% children who receive a caution do not go on to reoffend within 12 months.[11] In fact, offending by children is often a short-lived phase:[12] in 2016 the rate of offending per 100,000 of the population aged 15-17 years was four and a half times higher than that for those aged 21 years or older (see NAYJ figure 6). Based on this, we believe diverting children away from the youth justice system, recognising mistakes as part of growth and addressing the root-causes of youth offending is a more proactive approach to preventing and reducing (re)offending.

Deferred Prosecution

The criminogenic nature of custody and the utility of diverting young people from the justice system is also recognised in both the Taylor and Lammy reviews. The Lammy review recommends the introduction of deferred prosecution in the youth justice system based on the success of the Operation Turning Point pilot in the West Midlands. The project offered offenders the “opportunity to go through a programme of structured interventions, including, for example, drug or alcohol treatment. Those successfully completing their personalised programme would see the prosecution dropped, while those who did not would face criminal proceedings.”[13] Those accused of violent offences were 35% less likely to engage in serious reoffending after participating in the programme suggesting that deferred prosecution of this kind reduces the risk of reoffending to the public by addressing the root-causes of an individual’s challenging behaviour.

We welcome interventions like the above which address the root causes of offending without exacerbating an individual’s social exclusion in the same way imprisonment does.

Problem-solving courts

The Charlie Taylor Review recommends the creation of Children’s panels made up of three lay magistrates which investigates the causes of a child’s behaviour, including any health, welfare and education concerns, and puts together a plan to tackle those causes. The child, their parents/carers, a keyworker from the local authority and/or any other professionals the Panel require will be involved in the process of putting together and monitoring the child’s progress.[14] As highlighted by Charlie Taylor, “a key factor in children stopping offending is feeling that they are held in mind by somebody of substance who has their best interests at heart and believes they can change.”[15]

Similarly, the Lammy Review recommends the creation of Local Justice Panels which involve the local community in the decision-making process.[16]Together all those involved in the Local Justice Panel hold local services to account for their role in a child’s rehabilitation.

Given what we know about the risk factors that exacerbate the likelihood of engaging in criminal behaviour amongst young people, namely the fact that many of the causes of criminal behaviour lie beyond the youth justice system, Khulisa welcomes the adoption of a multiagency welfare-based response to youth offending.

School-based interventions

Our approach to preventing (re)offending is based on the strong link between social exclusion, antisocial behaviour and offending.

While recommendations based on the diversion of young people from the criminal justice system at the first point of contact are welcome, Khulisa calls for the prioritisation of early prevention-based interventions in schools and pupil referral units as the key solution to preventing and reducing offending.

As highlighted above, children who offend often have health, education and social care needs, which if left unmanaged, continue to deepen and entrench a young person’s exclusion from society. Faced with limited skills and resources to support children with complex needs many schools turn to exclusion as a means of dealing with children’s challenging behaviour.

Our approach to preventing (re)offending is based on the strong link between social exclusion, antisocial behaviour and offending. Statistics show that:

- More than 40% of 16-18 year olds who are NEET have previously been excluded from school. [17]

- Excluded pupils are 4 times more likely to be imprisoned as an adults [18]

- 88% of young offenders were excluded from school and most were 14 or younger when they last attended school. [19]

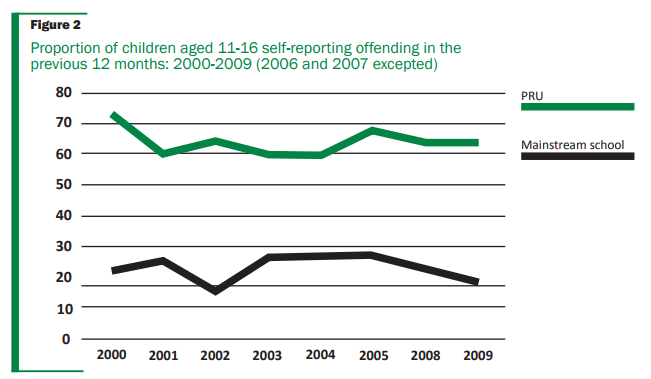

- Children who attend PRUs are on average 40% more likely to self-report engagement in criminal activity than those attending school[20]

We intervene at this key high-risk transition point to help young people learn and adopt new coping mechanisms to manage anger, improve concentration and their develop their executive functioning skills. Through our trauma-informed interventions like ‘Face It’ and ‘Tug of War’ we work with young people both independently and together with their teachers, families and carers to help them identify, understand and tackle the root-causes of disruptive behaviour. We also equip teachers, parents and carers with new techniques to manage challenging behaviour in a restorative and trauma-informed culture in the school and home.

Both internal and external evaluations of our work show that our programmes are successful in supporting young people’s reintegration into society and their desistance from challenging behaviour and crime. A 2016 evaluation of our ‘Face It’ programme (including data for 103 pupils) found:[21]

- 98% of participants reported a positive impact on behaviour – With 57% demonstrating a ‘significant improvement’

- 79% developed stronger, social connections

- 91% were reported to be in school & performing well 12 months after the programme

- ‘Face It’ decreased anger and hostility (including verbal and physical aggression)

- ‘Face It’ had a positive impact on how young people responded to stressful events

In adopting a welfare and asset-based approach to disruptive behaviour in children, we have and continue to be successful in helping young people break the cycle of crime and challenging behaviour in their lives. Our impact continues to strengthen our belief that early intervention work with young people is the key solution to preventing and reducing offending. Tackling the root cause of challenging behaviour early before behaviour becomes entrenched helps to reduce violence and prevent exclusion from school and/or entry into the criminal justice system.

Conclusion

Khulisa are committed to understanding ‘what works’ when supporting children and young adults with multiple and complex needs. Our approach to preventing (re)offending in young people is to tackle the belief patterns and behavioural factors that influence criminal behaviour in an environment that nurtures and restores young people.

Our experience, and the evidence highlighted above, has taught us that a predominantly risk-based approach, like imprisonment, has a lower impact on the succesful rehabilitation of children with complex needs and their longer-term chances of making a successful transition to a healthy, crime-free adulthood.

For this reason we welcome calls to divert young people away from the criminal justice system and are pleased to see calls for the adoption of problem-solving courts in the youth justice system. The adoption of a multi-agency, welfare-based framework for children who find themselves breaking the law is the first step to supporting longer-term outcomes such as education, employment, housing and drug and alcohol treatment.

Contact with the youth justice system is only one form of state intervention in the lives of children who engage in criminal behaviour. Schools, social and health care services along with their community are all very important determinants in improving outcomes for children concerned.

Khulisa welcomes these various calls for reform and will continue to advocate for the establishment of a welfare-based framework that is flexible and child-focused.

Footnotes

[1] Taylor, C., “Review of the Youth Justice System in England and Wales” Ministry of Justice (December 2016) page 2

[2] Ibid

[3] Ministry of Justice and Youth Justice Board (2016) Youth custody report: September 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/youth-custody-data

[4] Houses of Parliament Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology, “Education in Youth Custody Post Note” Number 524 (May 2016) https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/POST-PN-0524 p1

[5] Bateman, T., “The State of Youth Justice 2017: An Overview of Trends and Developments” National Youth Association for Youth Justice (2017) p10

[6] Lammy, D., “The Lammy Review: An independent review into the treatment of, and outcomes for, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic individuals in the Criminal Justice System” (2017) https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/643001/lammy-review-final-report.pdf p3

[7] Lennox, C., and Khan, L., “Youth justice” in “Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2012, Our Children Deserve Better: Prevention Pays” (2012) https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/252662/33571_2901304_CMO_Chapter_12.pdf p2

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] [1] Prison Reform Trust, “Prison: The Facts”, Bromley Briefings (Summer 2016) https://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/Portals/0/Documents/Bromley%20Briefings/summer%202016%20briefing.pdf p2

[11] Taylor Review, p4

[12] State of Youth Justice 2017 report, p20

[13] Lammy Review, page 29

[14] Taylor review, p30

[15] Taylor review p30

[16] Lammy Review, p31

[17] Atkinson, M., “Children’s Commissioner’s School Exclusions Inquiry: Call for Evidence” (2011) https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/10383/1/force_download.php%3Ffp%3D%252Fclient_assets%252Fcp%252Fpublication% 252F508%252FSchool_Exclusions_Inquiry_-_Call_for_evidence_-_adult_version.pdf p3

[18] Daily Record, “Excluded pupils four times more likely to end up in jail according to report” (2013) Daily Record https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/scottish-news/excluded-pupils-four-times-more-1724601

[19] Prime, R., “Children in Custody 2013-14: An Analysis Of 12-18 Year Olds’ Perceptions Of Their Experience In Secure Training Centres And Youth Offender Institutions” (2014) HM Inspectorate of Prisons Youth Justice Board https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2014/12/HMIPChildren-in-custody-2013-14-web.pdf p16

[20] State of Youth Justice 2017 report, p11

[21] [1] See: Gavrieldes, T., Nziadima, A., and Gouseti, I., “Khulisa Rehabilitation Social Action programmes Executive Summary” (2015) Restorative Justice for All and http://staging.khulisa.co.uk/who-are-we/our-impact/